Comprehensive holy-grail measurement tools like spatial transcriptomics represent an oncoming explosion in the data available in biology.

Scientists have always relied on indirect measures; when it comes to the realm of the microscopic, the hard-to-reach, or the otherwise unobservable, researchers have had to develop methods of studying physical phenomena using their impact on the surroundings. From using redshifting photons to study distant stars to radiocarbon-dating fossils to gauge their age, scientific techniques have often depended on indirect methods.

Except, every once in a while, some new technique will be developed that simply measures the properties of interest at a large scale. Such a technique is precisely what a group of ambitious researchers have published in Nature Methods, under the name “high-definition spatial transcriptomics (HDST)”. With this technique, samples of tissue can be processed to create digital “images” of cells in the locations and organization where they naturally exist. As a transcriptomic technique (i.e., a method to measure gene expression), this method also measures the gene expression in each cell, allowing researchers to get a full understanding of what cells are present in their sample and how they are arranged, all at once.

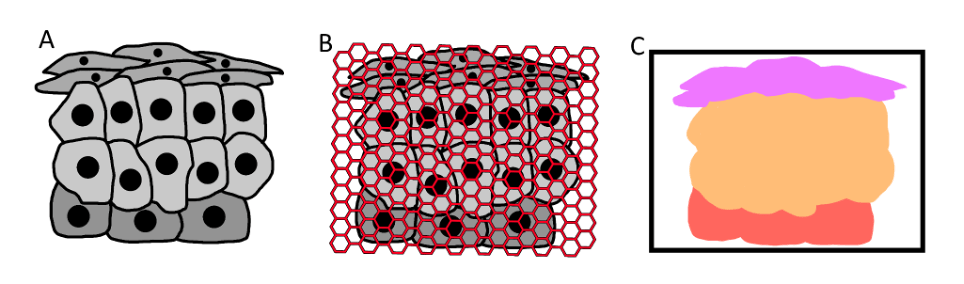

With a tissue sample of unknown cells (A), an HDST assay can analyse the tissue (B) and generate a digital representation of the tissue sample classified by cell type (C).

The potentialities of such a system may be massive. In the past, to markup a tissue sample in this multivariate way was an involved process; an experienced researcher would have to study a histologic sample, manually marking the edges of cells and classifying them. Not only was this approach very labour-intensive and require experience to interpret histologies (a task where even medical doctors can make mistakes), it also fundamentally relied on indirect measures. Whether it be cell shape or presence of specific proteins, some indicator would have to be used to determine which cell is which.

Not so with HDST: not only does it automate the work of labelling histologies, but it also quantifies gene expression levels throughout the tissue, meaning that cell type classifications are based on the exact theoretical basis that distinguishes them: the genes and the proteins that they express.

HDST achieves this measurement by combining several existing technologies. In essence, it is a scaled up and parallelized transcriptome assay. In this assay, the RNA in a sample is isolated, reverse transcribed into DNA, and then sequenced with Illumina high-throughput sequencing.

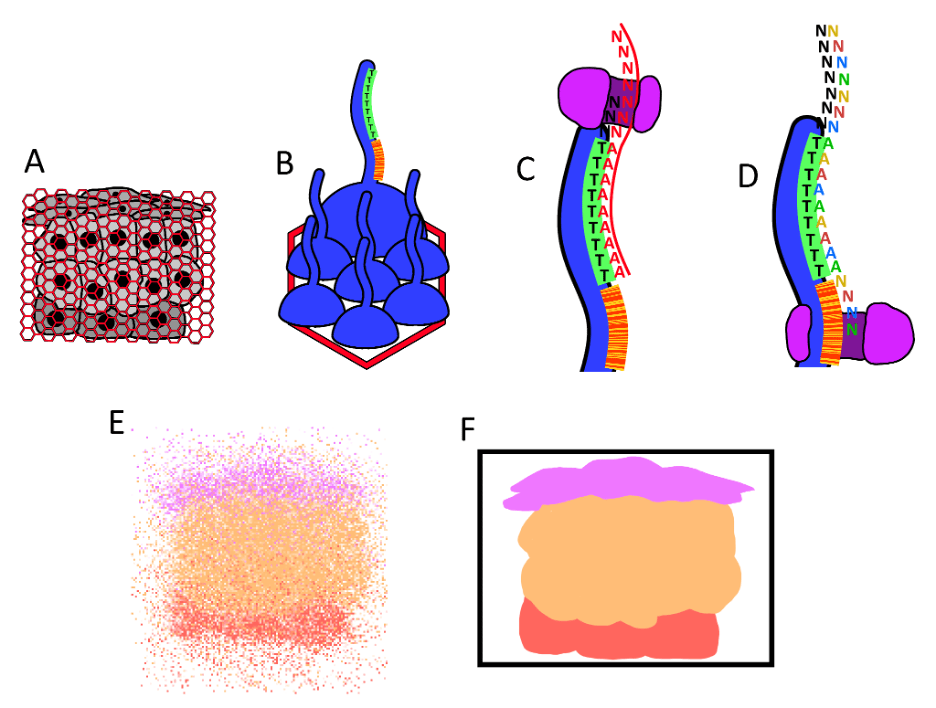

With HDST, researchers perform this process many times over in the wells of a custom assay. Each well in this assay captures RNA from nearby cells, which are then reverse transcribed into single-stranded DNA and bound to DNA sequences attached to beads in each well. These sequences all hold unique barcode sequences associated with their location of the assay, meaning that the extended final product holds both a barcode indicating their location on the sample and the sequence of the RNA expressed at that position. The final data appears as a cloud of different expressed RNA, that can then be processed to reveal a close approximation of the arrangement of cells in the sample and their expressed genes.

RNA from a tissue sample is bound to DNA sequences attached to beads comprising location-specific barcodes. The RNA is reverse-transcribed, sequenced with the Illumina technology, and processed to reveal the transcriptome of cells while presersving their arrangement.

In this way, HDST can be said to be a kind of cellular camera, taking transcriptomic “images” of tissue that hold gene expression information about every cell. When viewed in this context, HDST might only be one entry in a new trend of such cellular cameras; new technologies and methods that allow researchers a direct window into the biology that they are studying. In this new arena are technologies like high-throughput sequencers, revealing the entire genome of any sample; or wide-field calcium imaging, allowing neuroscientists to isolate neural activity for thousands of neurons through time and space.

These methods may represent a slow but oncoming revolution in biology, and perhaps science more broadly. It seems that cutting edge methods are increasingly more comprehensive and allow us to move further from the indirect and difficult-to-scale methods of the past. When the technology we use to study the properties of the universe becomes parallelized enough to measure many factors at once, while also scaling enough to do so for many elements at once, we have essentially created a camera into the universe. Only, this camera is not limited to the visible light spectrum. It can be designed to capture data of any type that we need.

Learn more about transcriptomics

- Methods and applications for single-cell and spatial multi-omics (Nature Reviews Genetics)

About the author

This post was written by Arvin Khoshboresh. Arvin is a recent graduate from the University of Toronto with a double major in neuroscience and molecular biology. He is interested in an interdisciplinary approach to biology by analyzing biological experiments with computer algorithms and machine learning, and is soon going to start a position in bioinformatics research. In his free time, he is an avid rock climber and photographer.

Great work Arvin, very happy to hear about your new research position

LikeLike