Huntington’s disease is associated with old age. Yet, recent research revealed that embryos may also display symptoms. Could understanding the early development of a disordered brain lead to a change in quality of life?

A 2020 study by Barnat et al. has found that Huntington’s disease can occur even before one is born. A stark contrast to the notion that the disease is associated with old age. Scientists discovered this by looking at the brains of donated human embryos, and specifically comparing those who had a Huntington’s disease genetic variant vs. those who did not.

For some background, George Huntington discovered the disease that bears his name in 1872. Huntington’s disease is a disorder that causes a progressive loss in motor functions, such as impaired posture and balance. It is also associated with psychiatric disturbances such as social withdrawal coupled with frequent thoughts of death; as well as cognitive defects that translate into a progressive loss of awareness. This leads to deficits in behavior like difficulties with organization and concentration. The mechanism of Huntington’s disease is thought to be the abnormal expansion of the trinucleotide CAG repeats in the huntingtin gene (often abbreviated HTT). Healthy individuals have 17–20 repeats, vs. above 35 repeats for patients suffering from Huntington’s disease.

Moreover, HD is acquired through an autosomal dominant fashion. Therefore, chances of developing Huntington’s disease depend on whether a parent carries the mutation. If this is the case, the child has a 50% probability of inheriting the mutated allele and the disease. Approximately 30,000 people of the US population are diagnosed with Huntington’s disease and 200,000 people are in peril of developing it. There are no treatments that can alter the course of this disease.

The study of Barnat et al. suggests that there is more to Huntington’s disease than neuro-degeneration. An earlier analysis by Nopoulous et al. (2011) identified a 4% decrease in the intracranial volumes of seven-year-olds who carry the mutation for Huntington’s disease. This notion aligns the claims of Barnat et al.’s that Huntington’s disease also carries a neuro-developmental component. Meaning that the effects of this disease can be detrimental even prior to adulthood, despite the fact that symptoms commonly appear between the ages of 30-40. Actually, Barnat et al. claim that HD may start as early as the fetus stage.

Huntingtin protein (HTT) and mutant huntingtin protein (mHTT). The CAG repeats encode a stretch of glutamine residues in the protein. This stretch has length 17–20 in healthy individuals and above 35 in Huntington’s disease patients.

As aforementioned, teh symptoms can occur even before birth. This is consistent with the information available from sites like alz.org, which describes that some of the earliest diagnosis of Huntington’s disease has been found at 2 years of age. This is the case of patient Karli Mukka who was first diagnosed in 2002. Initially, her movements on the entire left side of the body were slow, then she could no longer move and started to develop numerous problems, including the inability to jump, an irregular heartbeat, and a loss of speech (Lewis, 2013).

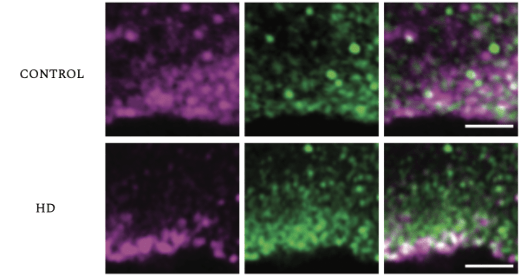

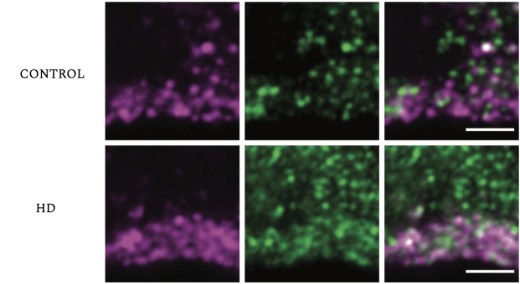

Cases such as this one inspired Barnat et al. to question if early events at the cellular level set the stage for later complications. The study used human fetuses at gestation week 13 (GW13), which were acquired from parents who carry a genetic variant of Huntington’s disease. The researchers also used mouse embryos for comparison. Huntingtin (HTT) protein is a protein that is important for development, whereby it acts in vesicular transport (the movement of molecular cargoes inside the cell). It is found throughout the body, especially in the brain and testes. In patients, HTT is mutated and is referred to as mutant huntingtin (mHTT). Barnat et al. state that mHTT hinders the function of many cellular processes such as endocytosis and Golgi-membrane trafficking. To show this, the researchers stained and compared the HTT protein with different components of developing cells that are important for endosomal trafficking, such as the trans-Golgi network, a protein known as early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), and transferrin receptors, which in mutant samples all overlapped to a significantly greater extent than with the controls Golgi-reassembly-stacking protein (GRASP65) and endoplasmic reticulum (calnexin). Thus, the mutant HTT protein may specifically interact with these factors to disrupt brain development.

The trans-Golgi network (TGN, Green) overlaps with HTT (purple) in cortical coronal sections of control (top) and mutant human fetus (bottom). The co-localization is higher in the control than in the mutant fetuses (HD).

Early Endosome antigen 1 (EEA1, Green) overlaps with HTT (purple) in coritcol coronal sections of control (top) and mutant human fetus (bottom). The control EEA1 does not co-localize to the same degree as HD EEA1 affected fetuses. The co-localization is higher in the control than in the mutant fetuses (HD).

Cell differentiation is dependent on moving up and down between the basal and apical ends of the cell, a process that is known as interkinetic nuclear migration. Interkinetic nuclear migration moderates the production of neural progenitor cells and neurogenesis. Huntington’s disease disrupts the proliferation of neural progenitor cells and leads to more premature specification of cell function. In the words of Barnat et al., “HTT protein regulates cell adhesion, polarity and epithelial organization”.

As previously stated, a key function of the HTT protein is to regulate other proteins, and essentially help them go where they need to go in the cell, a process known as membrane trafficking. If the HTT protein is unable to perform its normal functions, some structures such as tight-junctions are not assembled properly, preventing the cells from linking to one another.

Neuroepithelial junction proteins are regulated by HTT and are required for linking progenitor cells to one another, sealing the neuroepithelium. In Huntington’s disease, the integrity of the neuroepithelium is degraded, but what exactly does this mean? Suppose that junction proteins, when combined to form a complex, are not organized in the correct fashion. In this case, the apical junction complexes cannot perform their normal functions, meaning that the cell cycle is not progressing correctly, leading to premature neural progenitors.

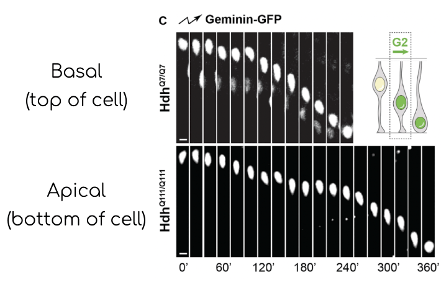

Moreover, a cell’s life cycle is defined by four key stages: Growth 1 (G1 Phase), Synthesis (S-phase), Growth 2 (G2-Phase), and Mitosis (M phase). During gestation week 13, mitosis commences at the apical surface of the ventricular zone, the nucleus of cells then undergoes a process known as G1-phase apical-to-basal migration. At the basal area of the ventricula zone, S-phase is completed and G2-phase from basal-to-apical surface begins mitosis again; this is important because the cell machinery required for the construction of the mitotic spindle is confined to the surface of the ventricular zone (see Arai & Taverna, 2017). Barnat et al. used a fluorescent ubiquitination-based cell cycle indicator (FUCCI) to follow the cell cycle phases. The cells affected with Huntington’s disease took longer to divide.

A time-lapse of G1-phase nuclei, ascending during interkinetic nuclear migration in both wild type mouse and knock-in mouse model where the first exon is human carrying 111 repeats.

A image time-lapse of G2-phase nuclei, descending during interkinetic nuclear migration in both wild type (HdhQ7/Q7) and knock-in mouse model where the first exon is human carrying 111 repeats.

Huntington’s disease is bad. It messes up a lot of cellular pathways that are important for brain development from the get-go. The complexity of this neurodegenerative disease seems simple, but there is more to discover. Studies such as that by Barnat et al. are the kind which propel curiosity and potential ideas for a cure.

Learn more about Huntington’s Disease:

- Huntington’s disease; what research is being done?

- Huntington’s Disease

- 2-Minute Neuroscience: Huntington’s disease

- Phases of the cell cycle

About the Author

Teddy Lvovsky is a determined fourth-year student at the University of Toronto majoring in Human Biology and Neuroscience and his future aspirations are in the field of research and medicine by pursuing an MD/Ph.D. Also, as a member of the Canadian Armed Forces serving and protecting the people is one of his great pleasures.

References

Arai, Y. & Taverna, E. (2017). Neural Progenitor Cell Polarity and Cortical Development. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:384. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00384

Barnat, M., Capizzi, M., Aparicio, E., Boluda, S., Wennagel, D., Kacher, R., Kassem, R., Lenoir, S., Agasse, F., Braz, B. Y., Liu, J. P., Ighil, J., Tessier, A., Zeitlin, S. O., Duyckaerts, C., Dommergues, M., Durr, A., & Humbert, S. (2020). Huntington’s disease alters human neurodevelopment. Science (New York, N.Y.), 369(6505), 787–793. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax3338

Bhattacharyya K. B. (2016). The story of George Huntington and his disease. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 19(1), 25–28. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-2327.175425

Lewis, R. (2020). Juvenile Huntington’s Disease: The Cruel Mutation – Simple Tech R. M., Third annual Hope Walk to fight Huntington’s disease | Medical News – Better information. Better health. Juvenile Huntington’s disease: The cruel mutation. DNA Science. https://dnascience.plos.org/2013/05/30/juvenile-huntingtons-disease-the-cruel-mutation/

Nopoulos, P. C., Aylward, E. H., Ross, C. A., Mills, J. A., Langbehn, D. R., Johnson, H. J., Magnotta, V. A., Pierson, R. K., Beglinger, L. J., Nance, M. A., Barker, R. A., & Paulsen, J. S. (2010). Smaller intracranial volume in Prodromal Huntington’s disease: Evidence for abnormal neurodevelopment. Brain, 134(1), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq280

Warby, S. C., Montpetit, A., Hayden, A. R., Carroll, J. B., Butland, S. L., Visscher, H., Collins, J. A., Semaka, A., Hudson, T. J., & Hayden, M. R. (2009). CAG expansion in the Huntington disease gene is associated with a specific and targetable predisposing haplogroup. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 84(3), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.02.003

Acknowledgements

Large gratitude to Dr. Guillaume Filion and volunteer TA Kyle Valentino who have provided the tools to break down and comprehend scientific literature, a skill I shall continue to hone throughout my life. Also a dear friend who goes by the name of Tasdid Sarker who has kept up the motivation and excitement to power through a tough semester.

Great work Teddy, thank you for setting stage on why this research is so important and explaining the findings of the article. Hope you achieve your goals 🙂

LikeLike